Power to Weight Ratio in Powerlifting: The Science of Relative Strength

Lifting heavy is impressive, but lifting heavy at a light bodyweight is elite. Learn how to calculate your Wilks Score, understand relative strength standards, and dominate the platform.

Azeem Iqbal

Performance Analyst

Table of Contents

- Power to Weight Ratio in Powerlifting: The Science of Relative Strength

- Absolute vs. Relative Strength (The Ant vs. The Elephant)

- The Formulas: Wilks, DOTS, Sinclair, and IPF GL Points

- Analyzing Strength Standards (1.5x, 2x, 3x Bodyweight)

- The Square-Cube Law: Why Smaller Lifters are “Relatively” Stronger

- Improving Your Score: Cutting Weight vs. Bulking Up

- Conclusion

Power to Weight Ratio in Powerlifting: The Science of Relative Strength

In the gym, the biggest guy loading up average plates often gets less respect than the smaller lifter moving a mountain of iron. This is the essence of Relative Strength.

Powerlifting is a sport defined by numbers: the Squat, the Bench Press, and the Deadlift. But the most important number isn’t always the Total—it’s the Total divided by the lifter’s body weight. This is the Power to Weight Ratio, and it is the great equalizer that allows a 60kg lifter to compete against a 140kg giant.

Absolute vs. Relative Strength (The Ant vs. The Elephant)

To understand powerlifting scoring, we must distinguish between two types of strength:

- Absolute Strength: The maximum amount of force an organism can exert, regardless of muscle or body mass.

- The Elephant: Can crush a tree. Massive absolute strength.

- Relative Strength: The amount of force exerted in relation to body mass.

- The Ant: Can lift 50x its body weight. Incredible relative strength.

In powerlifting, the Super Heavyweights (SHW) usually hold the records for Absolute Strength. They lift the most weight. But the Lighter Weight Classes often possess superior Relative Strength. They lift the most per kilogram of body mass.

The Formulas: Wilks, DOTS, Sinclair, and IPF GL Points

Simply dividing weight lifted by body weight ($Total / BW$) is flawed. It unfairly favors smaller lifters due to the Square-Cube Law (explained below). To fix this, powerlifting federations use coefficients to normalize scores.

The Wilks Coefficient

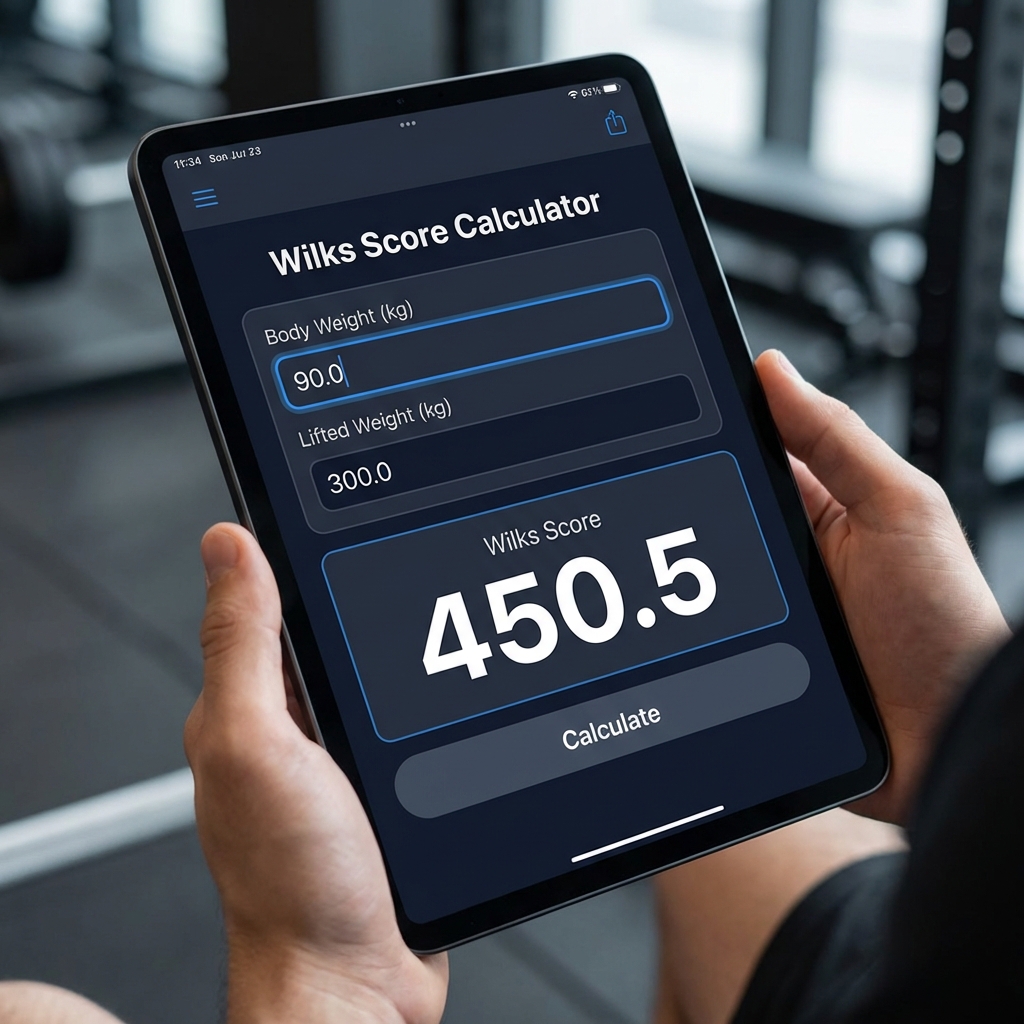

For decades, Wilks was the gold standard. It uses a complex polynomial equation to compare lifters of different body weights.

- How it works: A 60kg lifter totaling 400kg might have a Wilks of 350. A 100kg lifter totaling 600kg might also have a Wilks of 350. They are considered “equally strong.”

DOTS and IPF GL Points

Recently, the sport has moved away from Wilks. Analysis showed Wilks favored middle-weight lifters too much.

- DOTS: Corrects biases in Wilks, providing a fairer comparison for very light and super heavy lifters.

- IPF GL Points: The official formula of the International Powerlifting Federation, updated regularly based on real competition data.

Analyzing Strength Standards (1.5x, 2x, 3x Bodyweight)

If you don’t want to calculate complex coefficients, simple bodyweight multipliers are great for setting goals. Here are the “Gold Standards” for a drug-free male lifter (Female standards are typically ~65-70% of these):

1. The Squat

- Decent: 1.5x Bodyweight (e.g., 80kg male squatting 120kg)

- Strong: 2.0x Bodyweight (e.g., 80kg male squatting 160kg)

- Elite: 2.5x Bodyweight+

2. The Bench Press

- Decent: 1.0x Bodyweight (e.g., 80kg male benching 80kg)

- Strong: 1.5x Bodyweight (e.g., 80kg male benching 120kg)

- Elite: 2.0x Bodyweight (Rare!)

3. The Deadlift

- Decent: 1.75x Bodyweight

- Strong: 2.5x Bodyweight

- Elite: 3.0x Bodyweight (The “Triple Bodyweight Deadlift” is a massive milestone)

The Square-Cube Law: Why Smaller Lifters are “Relatively” Stronger

Why do we need Wilks? Why can’t we just use $Weight / Mass$? It comes down to physics.

- Strength is roughly proportional to the cross-sectional area of a muscle (2 Dimensions: Length $\times$ Width).

- Mass is proportional to Volume (3 Dimensions: Length $\times$ Width $\times$ Height).

As an athlete gets larger, their Mass increases faster (cubed) than their Strength (squared). This means a 2x larger athlete will be roughly 4x stronger but 8x heavier. Their power-to-weight ratio naturally drops. This is why ants can lift 50x their weight, but elephants cannot lift 50 elephants. Calculators like Wilks adjust for this biological reality, allowing us to see that a 400kg Deadlift at 180kg bodyweight is less impressive than a 300kg deadlift at 70kg bodyweight.

Improving Your Score: Cutting Weight vs. Bulking Up

Every powerlifter eventually faces the choice: Should I cut to a lower weight class to improve my ratio, or bulk up to get stronger?

The Case for Bulking

“Mass moves mass.” Gaining weight (even some fat) improves leverages. A bigger belly can help rebound out of a squat. More muscle mass has a higher potential for force production.

- Strategy: If you are tall and lanky, you need to fill out your frame. Your ratio involves getting stronger faster than you get heavier.

The Case for Cutting

If you are carrying 25%+ body fat, you have “dead weight.” You are fighting gravity in the squat and deadlift without that mass helping you lift.

- Strategy: Slow cut. Losing fat while maintaining muscle will skyrocket your Wilks score. A lifter who drops from 100kg to 90kg while keeping their Total the same has arguably become a “better” lifter.

Conclusion

Power to Weight Ratio transforms powerlifting from a contest of “who is the biggest” to “who is the most efficient.” Whether you track Wilks, DOTS, or just simple multipliers, improving your relative strength is the key to longevity and health in the sport. Lift heavy, but lift smart.

? Frequently Asked Questions

What is a good Wilks score?

Is Wilks or DOTS better?

How much should I squat for my weight?

Does gaining weight increase my total?

What is the strongest power to weight ratio ever?

Should I cut weight for a meet?

About Azeem Iqbal

We are dedicated to providing accurate tools and information to help you optimize performance and understand power-to-weight metrics.